Commanders

The two principal antagonists who confronted each other during the Battle of Normandy were General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, and General Erwin Rommel, Field Commander of the sector and the inspector general of the Atlantic Wall defenses.

General Dwight Eisenhower together with soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division

Eisenhower had graduated from West Point in 1915. He had not participated in World War I, which he passed training recruits in the United States. Rommel, on the other hand, had lived it intensely on the Italian and French front, earning himself high decorations for his demonstrated courage and skills.

During World War II Rommel acquired notable prestige as commander of armored forces in France in 1940 and then as head commander of the German contingent in North Africa, known as Afrika Korps, until 1942.

In this theater he obtained important successes against the Allies, so as to be nicknamed the “Desert Fox.” Numerous and grave defeats, due to the enormous disparity of field forces, determined the capitulation of the Axis forces in North Africa and the definitive abandon of the theater of war.

Eisenhower reached North Africa in 1942 as head commander of the Allied forces in that theater.

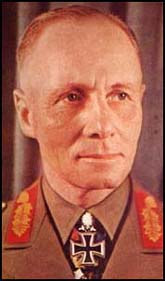

General Erwin Rommel

Rommel was a veteran, while Eisenhower had never participated in combat. The consequences and implications of this difference are perhaps less obvious than they seem.

At the dawn of D-Day Rommel was an embittered general, without any faith in the entire structure of German command and animated by a profound contempt for his own head commander, Adolf Hitler. The experience as veteran also made him too prudent and hesitant in several situations. All of these elements perhaps can explain why a commander of armored forces did not seek to obstruct Hitler’s will to build enormous fixed defenses, bunkers and trenches, undertaking a defensive war campaign instead of one based on mobility.

Even if he had not opposed Hitler’s rise to power and appreciated the military and political journey that had brought Germany back to the status of a world power, Rommel was not a Nazi and his promotion had always been motivated by merit.

He believed in fighting for his own country and like many other German commanders he had cultivated over the years the conviction that Hitler’s choices were bringing the country to ruins. The defeat of D-Day increased his anxiety even more and he participated in the conspiracy of July 20, 1944 against Hitler. Following the failure of the attack, Hitler forced Rommel to commit suicide.

Eisenhower had full faith in the structure of Allied command and in the institutions of his country. He was an optimist and circulated a vision of the facts, even in moments of crisis, always constructive and positive. He had earned himself the esteem and respect of the subordinates of the staff and of the troops in general, despite that he had no fighting experience. He was an excellent leader and diplomat.

He was aware of having undertaken a struggle that did not only regard two military arrays, but two different visions of life and the world.

Eisenhower became President of the United States in 1953 and governed the country for two consecutive terms until 1961.